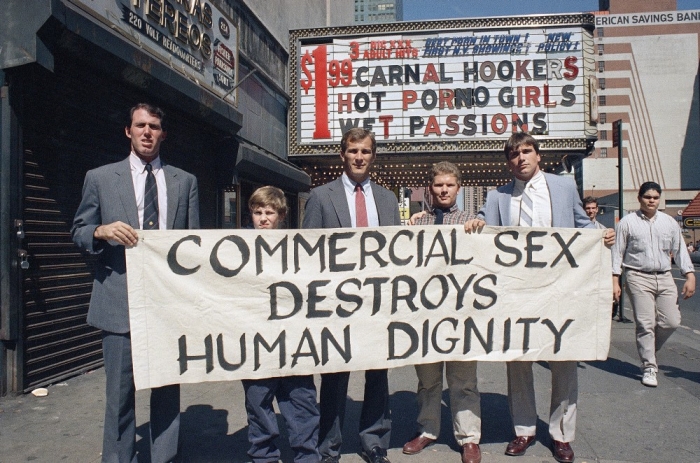

Obscenity refers to a narrow category of pornography that violates contemporary community standards and has no serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value. For adults at least, most pornography receives constitutional protection. In this 1987 photo, an anti-pornography protest takes place in New York's Time Square. (Photo by Mario Cabrera/Associated Press)

Obscenity refers to a narrow category of pornography that violates contemporary community standards and has no serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

For adults at least, most pornography — material of a sexual nature that arouses many readers and viewers — receives constitutional protection. However, two types of pornography receive no First Amendment protection: obscenity and child pornography. Sometimes, material is classified as “harmful to minors” (or obscene as to minors), even though adults can have access to the same material.

Obscenity remains one of the most controversial and confounding areas of First Amendment law, and Supreme Court justices have struggled mightily through the years to define it. Justice Potter Stewart could provide no definition for obscenity in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), but he did exclaim: “I know it when I see it.” Stewart found that the court was “faced with the task of trying to define what may be indefinable.” In a later case, Interstate Circuit, Inc. v. Dallas (1968), Justice John Marshall Harlan II referred to this area as the “intractable obscenity problem.”

Several early U.S. courts adopted a standard for obscenity from the British case Regina v. Hicklin (1868). The Hicklin rule provided the following test for obscenity: “whether the tendency of the matter . . . is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall.”

This test allowed material to be declared obscene based on isolated passages of a work and its effect on particularly susceptible persons. Using this broad test, the British court ruled obscene books deemed to be anti-religious.

The two major problems with the Hicklin test were that it allowed works to be judged obscene based on isolated passages, and it focused on particularly susceptible persons instead of reasonable persons. This focus led to suppression of much free expression.

The Supreme Court squarely confronted the obscenity question in Roth v. United States (1957), a case contesting the constitutionality of a federal law prohibiting the mailing of any material that is “obscene, lewd, lascivious, or filthy . . . or other publication of an indecent character.” The court, in an opinion drafted by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., determined that “obscenity is not within the area of constitutionally protected speech or press.”

He articulated a new test for obscenity: “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.” The Roth test differed from the Hicklin test in that it focused on “the dominant theme” of the material as opposed to isolated passages and on the average person rather than the most susceptible person.

The Supreme Court struggled with obscenity cases through the 1960s and 1970s. In Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), a plurality of the Court, in an opinion by Justice Brennan, articulated a new three-part test:

In the 1970s, the Burger Court determined that the obscenity standard was too rigid for prosecutors. Therefore, in Miller v. California (1973) the Supreme Court adopted a new three-part test — what Chief Justice Warren E. Burger called “guidelines” for jurors — that was more favorable to the prosecution:

In Miller, the court reasoned that individuals could not be convicted of obscenity charges unless the materials depict “patently offensive hard core sexual conduct.” Under that reasoning, many sexually explicit materials — pornographic magazines, books, and movies — are not legally obscene. Ironically, Justice Brennan dissented in Miller and Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973), changing his position on obscenity. He determined that obscenity laws were too vague and could not be applied without “jeopardizing fundamental First Amendment values.”

The Miller test remains the leading test for obscenity cases, but it continues to stir debate.

In its 1987 decision in Pope v. Illinois (1987), the Supreme Court clarified that the “serious value” prong of the Miller test was not to be judged by contemporary community standards. Obscenity prosecutions do, however, impose contemporary community standards, even though a distributor may transport materials to various communities. Thus interesting issues emerge when a defendant in California is prosecuted in a locale with more restrictive community standards.

This phenomenon has caused some legal experts and interested observers to call for the creation of a national standard, particularly in the age of the internet.

In Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union (2002), several justices expressed concern about applying local community standards to the internet as required by the Child Online Protection Act of 1998. For example, Justice Stephen G. Breyer wrote in his concurring opinion that “to read the statute as adopting the community standards of every locality in the United States would provide the most puritan of communities with a heckler’s veto affecting the rest of the Nation.”

Similarly, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, in her concurrence, wrote that “adoption of a national standard is necessary in my view for any reasonable regulation of Internet obscenity.”

The Supreme Court has resisted efforts to extend the rationale of obscenity from hard-core sexual materials to hard-core violence.

The state of California sought to advance the concept of violence as obscenity in defending its state law regulating the sale or rental of violent video games to minors. The Supreme Court invalidated the law in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2011) , writing that “violence is not part of the obscenity that the Constitution permits to be regulated.”

Federal obscenity prosecutions increased during the George W. Bush administration. States continued to pursue obscenity prosecutions against hard-core pornography, but also occasionally against other materials. For example, in 1994 a comic book artist was convicted of obscenity in Florida, and in 1999 the owner of gay bar in Nebraska was successfully prosecuted for displaying a gay art in a basement. Although obscenity laws have their critics, they likely will remain part of the legal system and First Amendment jurisprudence.

State obscenity prosecutions continue in the 21 st century. In this light, Professor Jennifer Kinsley refers to the argument that obscenity law is a thing of the past as “the myth of obsolete obscenity.”

David L. Hudson, Jr . is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.