The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made many substantial reforms to the tax code, but it left tax expenditures largely unchanged. A tax expenditure is a departure from the “normal” tax code that lowers a taxpayer’s burden, such as an exemption, deduction, or credit. They are called tax “expenditures” because, in practice, they resemble government spending.[1]

Many tax expenditures give preferential treatment for particular economic activities. These expenditures deviate from sound tax policy by making the tax code less neutral and shrinking the tax base. Some expenditures, however, are broad-based changes that move the U.S. toward a different tax system. These expenditures deserve closer scrutiny from policymakers.

A priority for future tax reform should be reviewing each tax expenditure and determining whether it serves a reasonable purpose and accomplishes that purpose in a reasonable way. Does it move us toward a different tax system? Is it spending on an important priority of society at large? Or does it narrowly provide a preference to a specific industry or activity? Answering these questions and classifying the expenditures is critical in determining which are worth keeping.

This paper reviews what tax expenditures are, the positive and negative effects they can have on the tax code, and the TCJA’s changes to tax expenditures.

The idea of the tax expenditure was developed in the 1960s by Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Stanley Surrey. It officially became part of the tax policy lexicon in 1974, when Congress mandated that tax expenditures be recorded as part of the annual budget. Under that act, tax expenditures were officially defined as “revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special exclusion, exemption, or deduction from gross income For individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” or which provide a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability.”[2]

This is a useful definition for highlighting spending on specific industries or social priorities and estimating the cost of including those provisions in the tax code. However, any measure of tax expenditures that begins from a particular tax system will always treat any change to it–no matter how broad–as a tax expenditure. It is therefore important to separate broad-based changes to the tax code from narrow preferences.

Given that a tax expenditure is defined as a departure from the “normal” tax code, the nature of tax expenditures depends crucially on what the “normal” tax code is. The Treasury Department and Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have adopted similar definitions, but while these definitions have been consistent, they are not economically coherent.

The federal tax system is built on a poor intellectual foundation; it relies heavily on a definition of income developed by economists Robert Haig and Henry Simons almost a century ago.[3] The Haig-Simons definition is that income equals the sum of your consumption and your change in net worth; I = C + ΔNW. This is a useful accounting identity. It tells us that what we don’t spend on consumption becomes accumulated saving. However, it is not necessarily a good tax base.

There is an issue with including both a person’s consumption (C) and his or her change in net worth (ΔNW) in the tax base. The issue is that a change in one’s net worth usually becomes consumption at a later date.[4] (For example, an average individual accumulates net worth throughout her working life and spends it down in retirement.) As a result, the Haig-Simons definition single-counts some kinds of consumption, but double-counts other kinds for the purposes of taxation.

A distortion like this one–where some kinds of economic production get taxed more than other kinds–is generally a drawback. But this particular distortion is unusually powerful because it artificially reduces the after-tax return to saving and investment. Since people’s saving and investment decisions are sensitive to expected after-tax returns, the result is substantially less capital formation, which means smaller increases over time in productivity, incomes, and employment.

There are, of course, alternative tax bases. Among these are sales taxes, value-added taxes, excise taxes, corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, and property taxes. All of these tax bases are used in various places around the world, and all have benefits and drawbacks. There is no objective reason to define any particular tax base as “normal” for the purposes of counting tax expenditures.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

The chosen “normal” tax code in Washington includes an individual income tax An individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. based on the Haig-Simons definition paired with a corporate income tax A corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. —although Simons regarded the corporate income tax as a double tax that he did not include in his definition of income. At times, government bureaus also measure tax expenditures from the payroll taxes that fund social insurance programs like Social Security.

Even after defining the “normal” tax base, there are still many issues in methodology. For example, measuring some changes in net worth (like capital gains) is a difficult problem. A taxpayer’s net worth may include assets with ever-changing values. For this reason, changes in asset value are usually only recorded as capital gains (or losses) upon the sale of the asset.

This is certainly a departure from a pure Haig-Simons income tax–and as a “deferral of tax liability,” it would be considered a tax expenditure under the Haig-Simons definition–but it is too difficult to calculate. As a result, it is usually not considered a tax expenditure, and the “normal” tax code measures changes in net worth only when they are realized.

This is one of the many compromises that the Treasury and JCT have to make in order to nail down a definition of tax expenditures. Some of these choices are extremely significant. For example, progressive income tax brackets A tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. are not counted as a “preferential rate of tax.” As a result, the official list of tax expenditures appears to favor wealthier taxpayers, because the progressivity of the tax system is already assumed in defining the base.[5]

Additionally, personal exemptions and the standard deduction The standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. are generally considered not to be tax expenditures, but rather part of a structure that defines a zero-rate bracket.[6] Personal exemptions are a particularly curious example, because they effectively lower the tax bill for adults with more dependents. Child tax credits, which serve the exact same purpose, are considered to be tax expenditures.

Additionally, the corporate income tax (at any rate Congress chooses) is considered “normal,” even though it is duplicative with income taxes on shareholders.[7] This corporate tax code gets deductions for employee compensation and a particular kind of deduction for capital costs, known as the alternative depreciation system (ADS).[8] There is no particular reason to believe that this deduction for capital costs is the only “normal” one, and the U.S. has in fact experimented with many different systems over the last century. ADS, however, was the method in use at the time that tax expenditures were invented as a concept.

Given all of these metaphysical questions about what constitutes a normal tax structure, the true nature of tax expenditures will always be somewhat subjective. The particular nature of what constitutes a tax expenditure in Washington is partially economics, partially one’s value judgments, and partially historical accident. However, rather than devising an alternative measure of tax expenditures, this report will concern itself with tax expenditures as measured in practice.

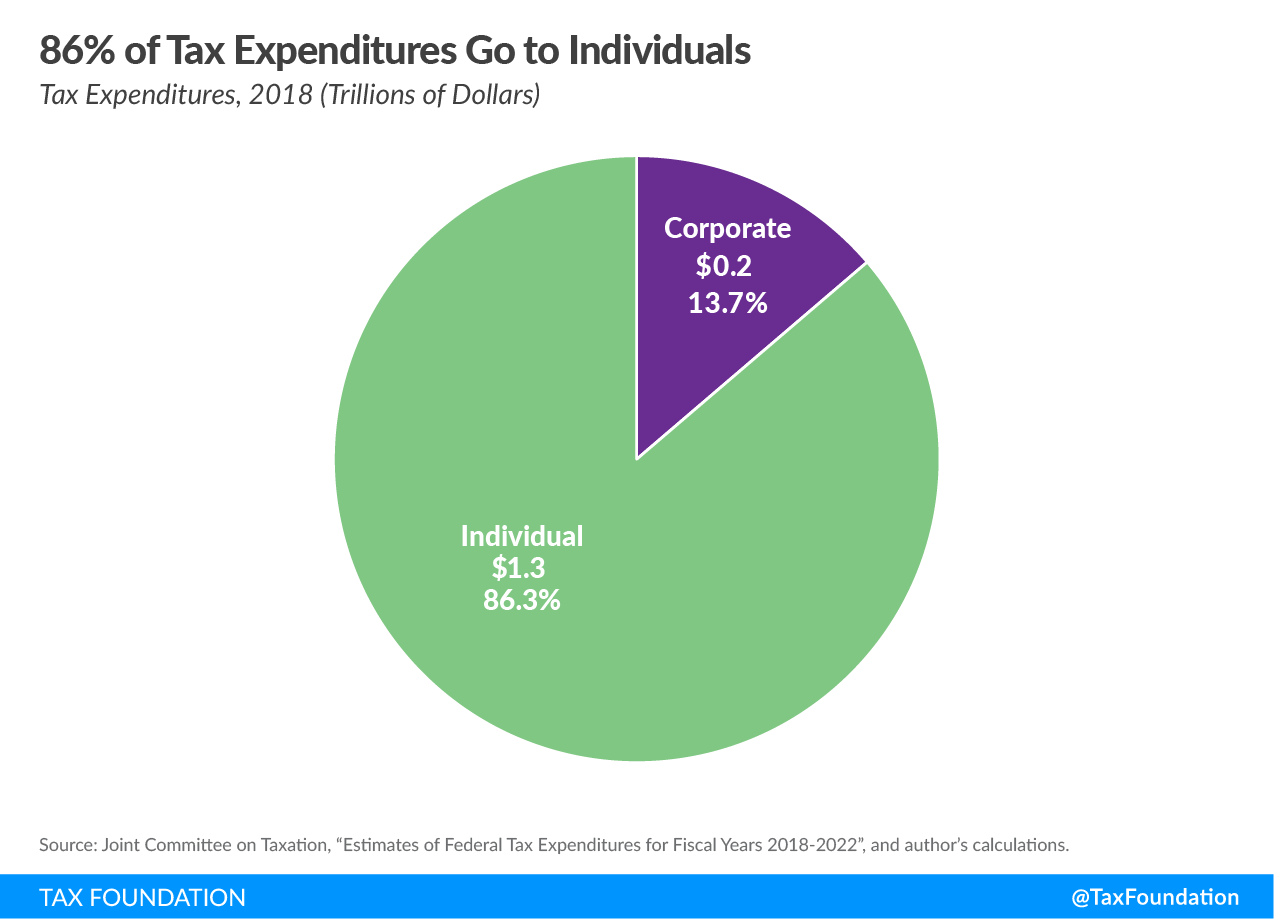

The majority of the expenses incurred by tax expenditures comes from the individual side. JCT estimates that individual expenditures will cost $1.3 trillion in 2018, or 86.3 percent of the total cost of all expenditures, while corporate expenditures will cost $0.2 trillion ($200 billion), or 13.7 percent, for a total of $1.5 trillion.[9]

Figure 1

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

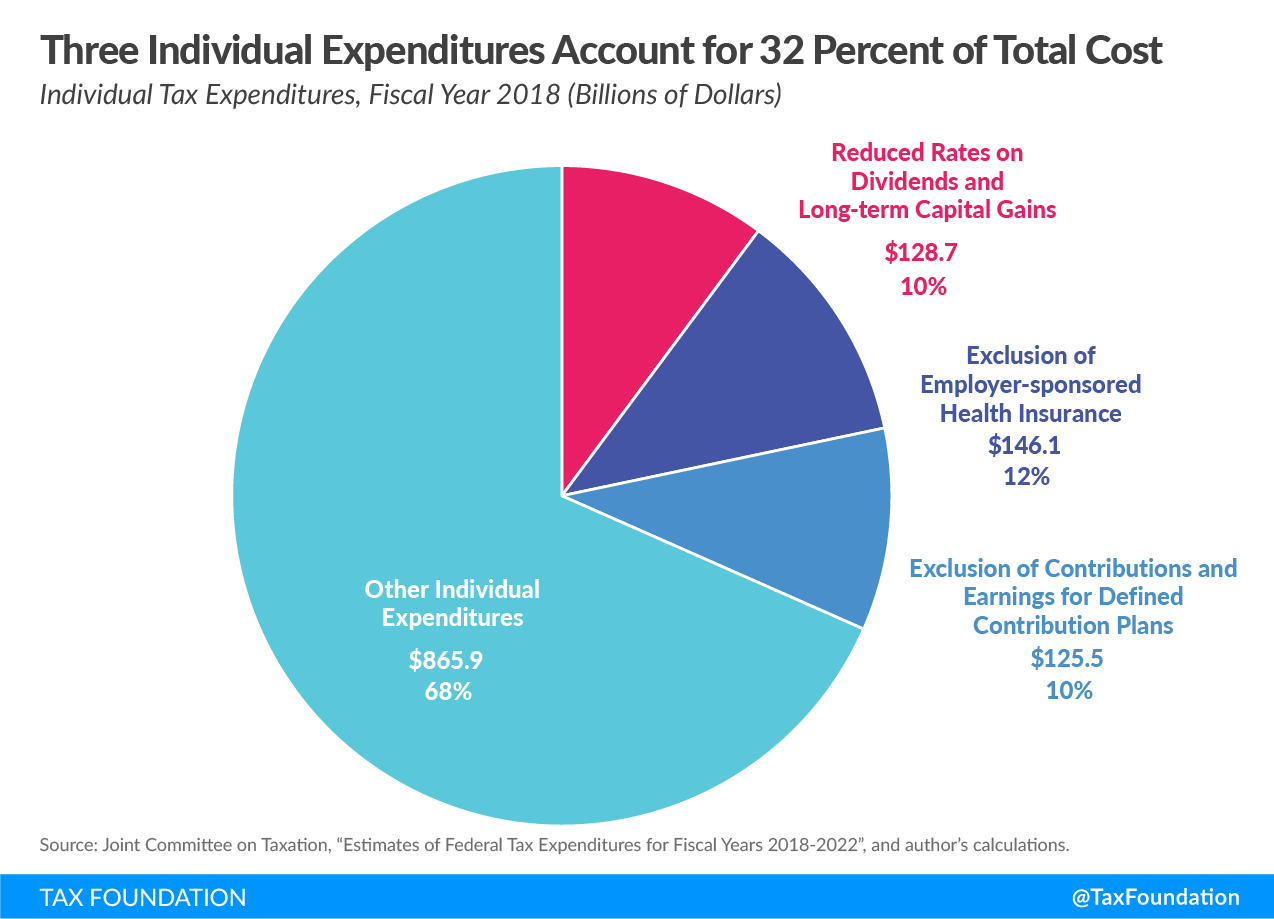

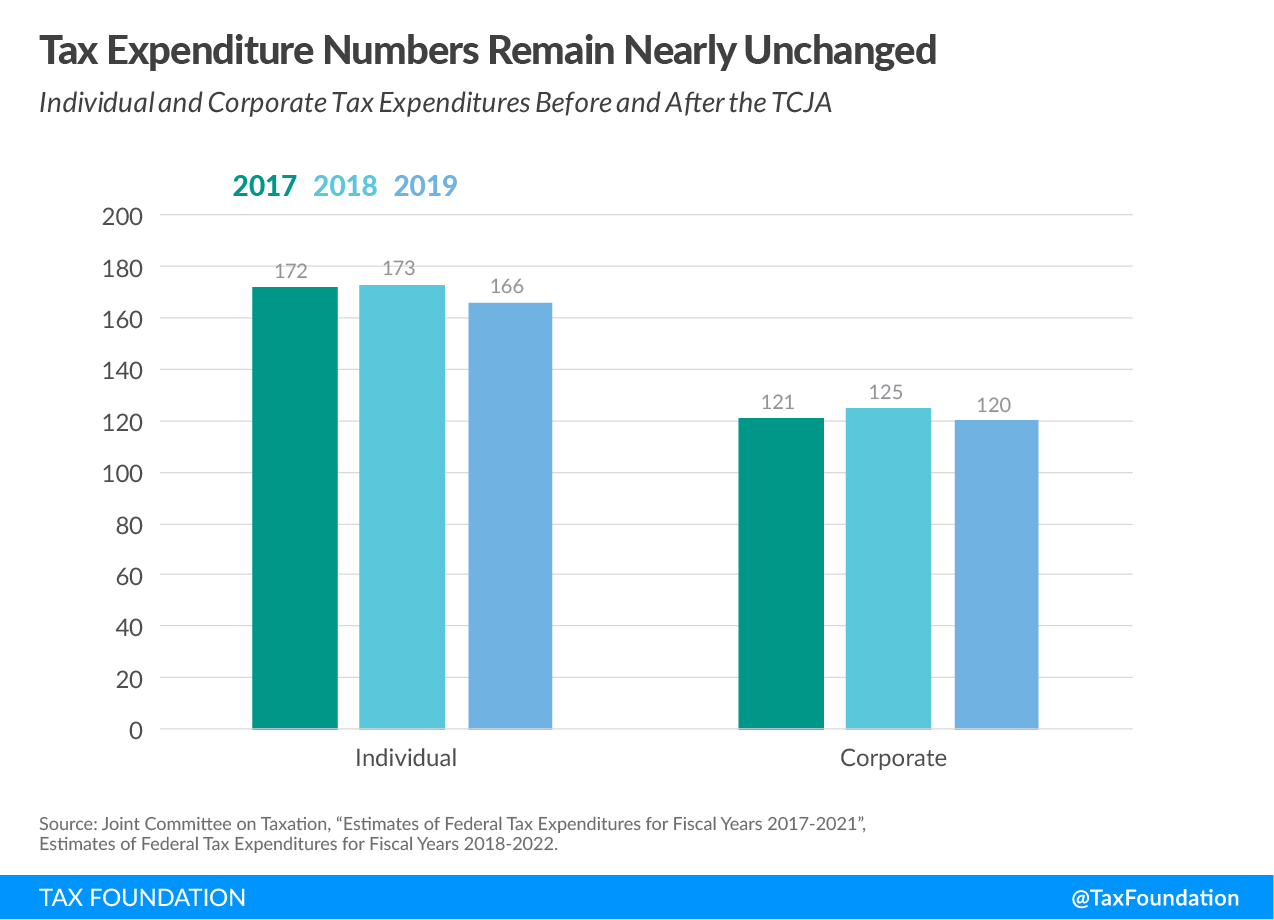

The TCJA increased the number of tax expenditures from 172 in 2017 (the year before the TCJA passed) to 173 in 2018.[10] Five tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, while six tax expenditures were added, resulting in a net increase.

Table 1 lists the new individual tax expenditures and their projected 2018 cost.

| Expenditure | 2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Note: A negative cost means that a provision is a negative tax expenditure, which raises revenue. JCT defines negative tax expenditures as “tax provisions that provide treatment less favorable than normal income tax law and are not related directly to progressivity.” Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021,” “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.” | |

| Limitation on net interest deduction to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income | -$0.9 |

| Insurance companies’ two-year NOL carryback | $0.2 |

| 20 percent deduction for qualified business income | $33.2 |

| Qualified opportunity zones | $0.4 |

| Credit for family and medical leave | $0.2 |

| Treatment of employee moving expenses | -$1.0 |

Table 2 lists the five individual tax expenditures that were eliminated or expired.

| Expenditure | 2017 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021.” | |

| Therapeutic research credit | $0.1 |

| Expensing of research and experimental expenditures | N/A |

| Treatment of income from exploration and mining of natural resources as qualifying income under the publicly-traded partnership rules | $0.1 |

| Exclusion of income attributable to the discharge of principal residence acquisition indebtedness | $2.4 |

| Deduction for higher education expenses | $0.4 |

However, several of the above provisions, such as the discharge of principal residence indebtedness and the deduction for higher education expenses, are likely to be extended for the 2018 tax year. These provisions, along with approximately 25 others, are generally extended on an annual basis as part of a package colloquially known as “extenders.”[11]

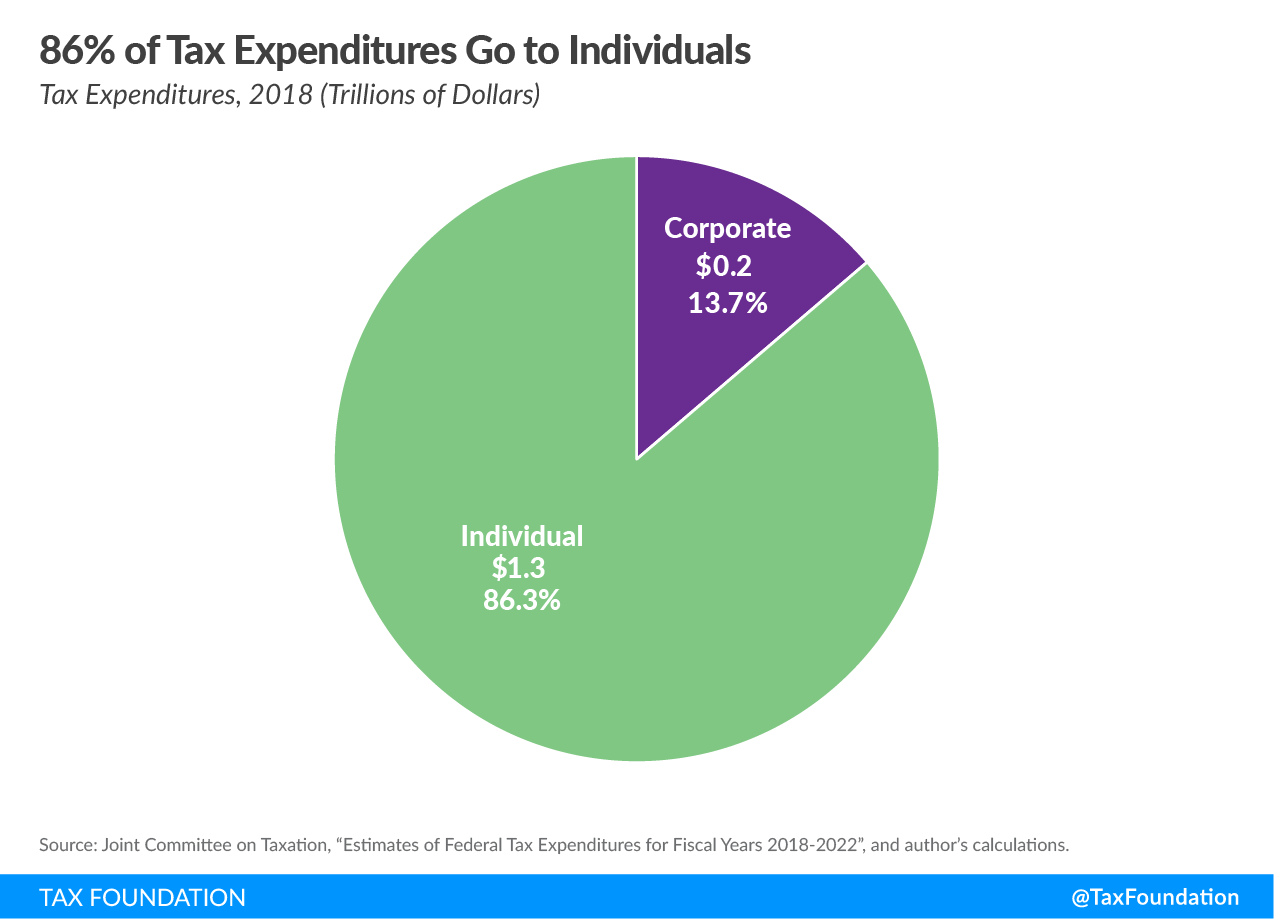

Figure 2 illustrates the largest individual tax expenditures for fiscal year 2018. Three tax expenditures make up roughly 32 percent of all individual tax expenditures. These expenditures are: the exclusion of employer contributions for health care, health insurance premiums, and long-term care insurance premiums; reduced rates of tax on dividends and long-term capital gains; and net exclusion of pension contributions. In total, individual tax expenditures are projected to cost $1.3 trillion in 2018.

Figure 2

This expenditure excludes employer-paid health insurance premiums, long-term care insurance, and other medical expenses from employee gross income. Employer contributions to insurance premiums reflect a tax preference for those taxpayers with employer-provided health insurance, because they receive a form of labor compensation that goes untaxed. Taxable income Taxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. would generally include all work compensation, including health benefits, under the baseline tax system.

This expenditure is also the clearest example of Congress prioritizing some economic activities over others. Health is no doubt important, but the use of the tax code to bundle employment together with health insurance is worthy of skepticism.[12]

Under the baseline tax system, tax rates on income would range from 10 percent to 37 percent, plus a 3.8 percent surtax A surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. for high-income individuals. This expenditure sets a maximum rate of 20 percent, plus the 3.8 percent surtax, for qualified dividends and capital gains on assets held for more than one year and qualified dividends.[13] This is listed as a tax expenditure because the normal tax code defined by JCT includes a full Haig-Simons individual income tax in addition to a corporate income tax. This tax expenditure, in some ways, returns to a pure Haig-Simons definition, because it acknowledges and compensates for the corporate income tax on the individual side.

This is an example of a reform that is clearly designed as a move toward a different kind of tax system (perhaps, an equal tax on all income with corporate integration) but it does not represent special tax treatment for a specific sector of the economy. Rather, it is a deliberate attempt to move the tax code past the definition of normalcy that was chosen in the 1970s.

This expenditure allows individual taxpayers and employers to make tax-preferred contributions to employer-provided 401(k)s and similar plans. In 2018, the employee exclusion limit for employees under age 50 is $18,500; for employees age 50 or over, the exclusion limit is $24,500. In 2018, the maximum exclusion for defined contribution plans, including both employee and employer contributions, is $55,000. The tax on both contributions and the investment income that plans earn is deferred until withdrawal.[14]

These are lowered tax burdens only in the sense that they are considered a “deferral” of tax liability from what is seen as the normal tax code. Many tax systems–like those for pensions in most countries, not just ours–defer tax liability on pension contributions until the money is paid. More broadly, this represents a move toward a style of tax known as the consumed income tax or inflow-outflow tax.[15]

Table 3 lists the seven individual tax expenditures that are scheduled to expire at the end of the 2018 tax year.

| Expenditure | 2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.” | |

| Credit for energy-efficient improvements to existing homes | $0.1 |

| Deduction for premiums for qualified mortgage insurance | $0.8 |

| Expensing of costs to remove architectural and transportation barriers to the handicapped and elderly | N/A |

| Deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities | $1.2 |

| Credit for Indian reservation employment | N/A |

| District of Columbia tax incentives | N/A |

| Parental personal exemption for students aged 19 to 23 | $1.1 |

Importantly, current law assumes temporary provisions will expire as scheduled. But for more than a decade, lawmakers have continually reauthorized a set of provisions known as “tax extenders,” instead of allowing them to expire or making them permanent.[16] If lawmakers continue their ad hoc reauthorization of extenders, tax expenditures in 2019 will be larger in number and cost.

Nevertheless, according to current law, which does not account for likely extensions, there will be 166 individual tax expenditures in fiscal year 2019, compared to 172 in 2017.

Figure 3

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

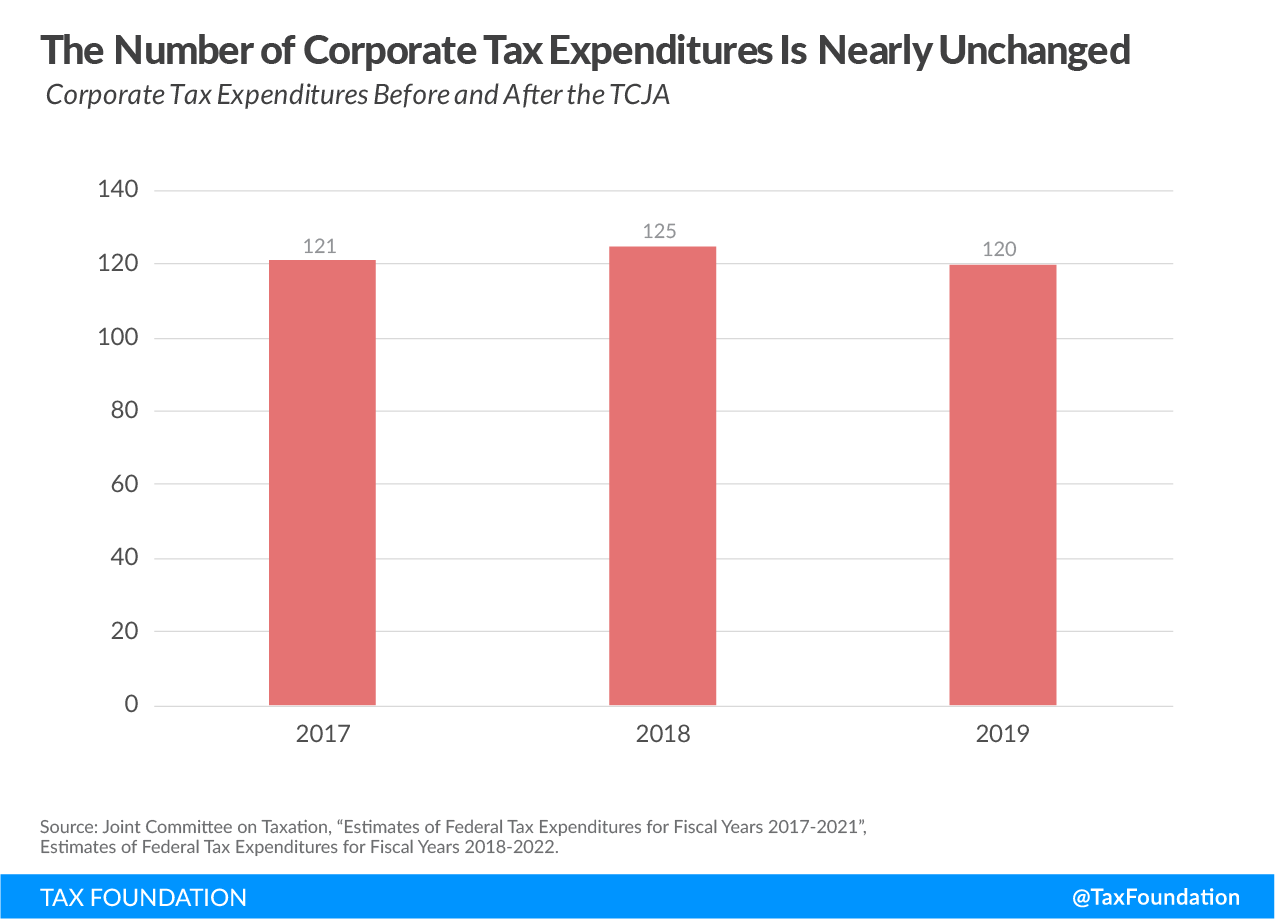

On the corporate level, the number of tax expenditures has increased as well, from 121 in 2017 to 125 in 2018. Five tax expenditures were eliminated or set to expire, while nine tax expenditures were added, resulting in a net increase.

Table 4 lists the new corporate expenditures and their projected 2018 cost.[17]

| Expenditure | 2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021,” “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.” | |

| Base erosion and anti-abuse tax | -$2.9 |

| Deduction for foreign-derived intangible income derived from trade or business within the United States | $9.6 |

| Limitation on deduction for FDIC premiums | -$0.7 |

| Limitation on net interest deduction to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income | -$8.8 |

| Insurance companies’ two-year NOL carryback | $2.0 |

| Treatment of employer-paid transportation benefits | -$1.5 |

| Qualified opportunity zones | $1.1 |

| Credit for family and medical leave | $0.5 |

| Treatment of meals and lodging (other than military) | -$0.8 |

Table 5 lists the five corporate tax expenditures that were eliminated or expired.

| Expenditure | 2017 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. A negative cost means that a provision is a negative tax expenditure, which raises revenue. The JCT defines negative tax expenditures as “tax provisions that provide treatment less favorable than normal income tax law and are not related directly to progressivity.” Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2017-2021.” | |

| Therapeutic research credit | $0.1 |

| Special rule to implement electric transmission restructuring | -$0.2 |

| Reduced rates on first $10 million of corporate taxable income | $3.1 |

| Net alternative minimum tax attributable to net operating loss limitation | -$0.4 |

| 50 percent tax credit for certain expenditures for maintaining railroad tracks | $0.2 |

As with individual tax expenditures, some of the above provisions, such as the railroad track maintenance credit, are extenders. Though scheduled to expire according to current law, they are likely to be retroactively extended for the 2018 tax year.[18]

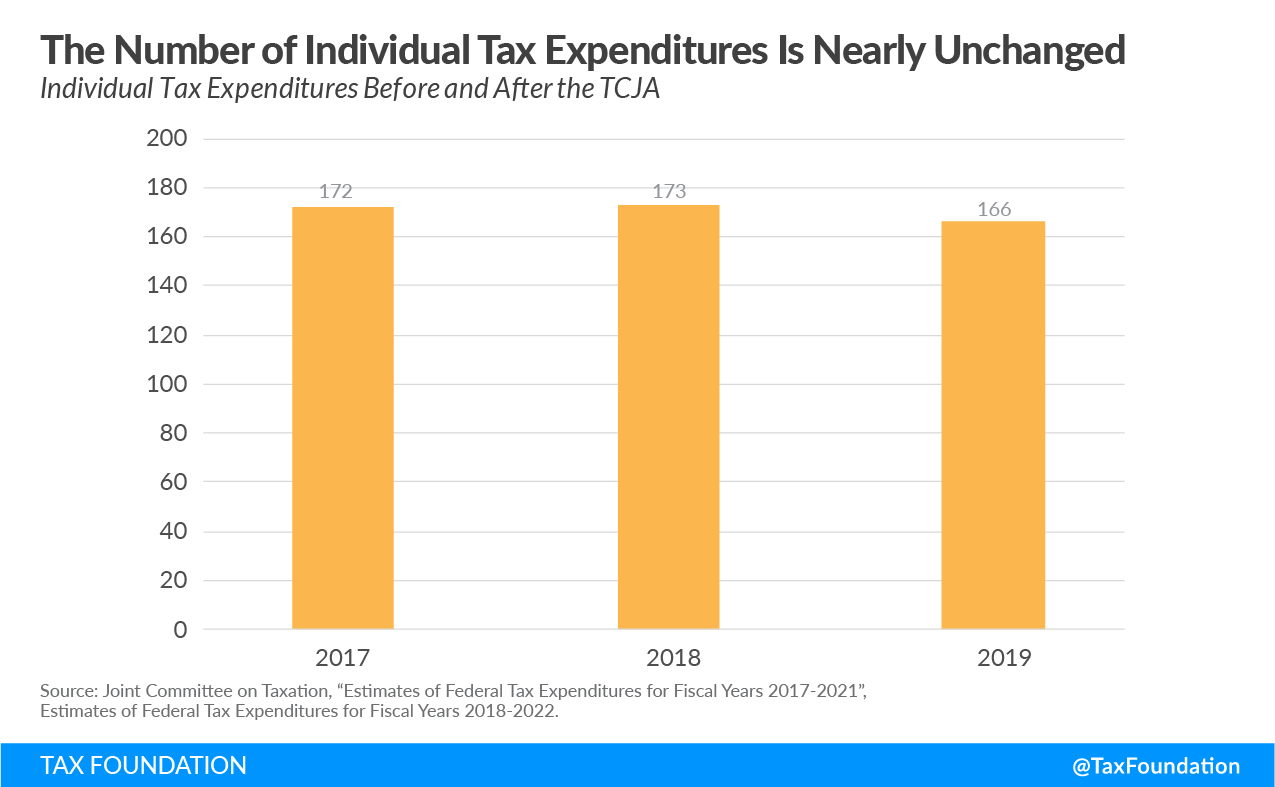

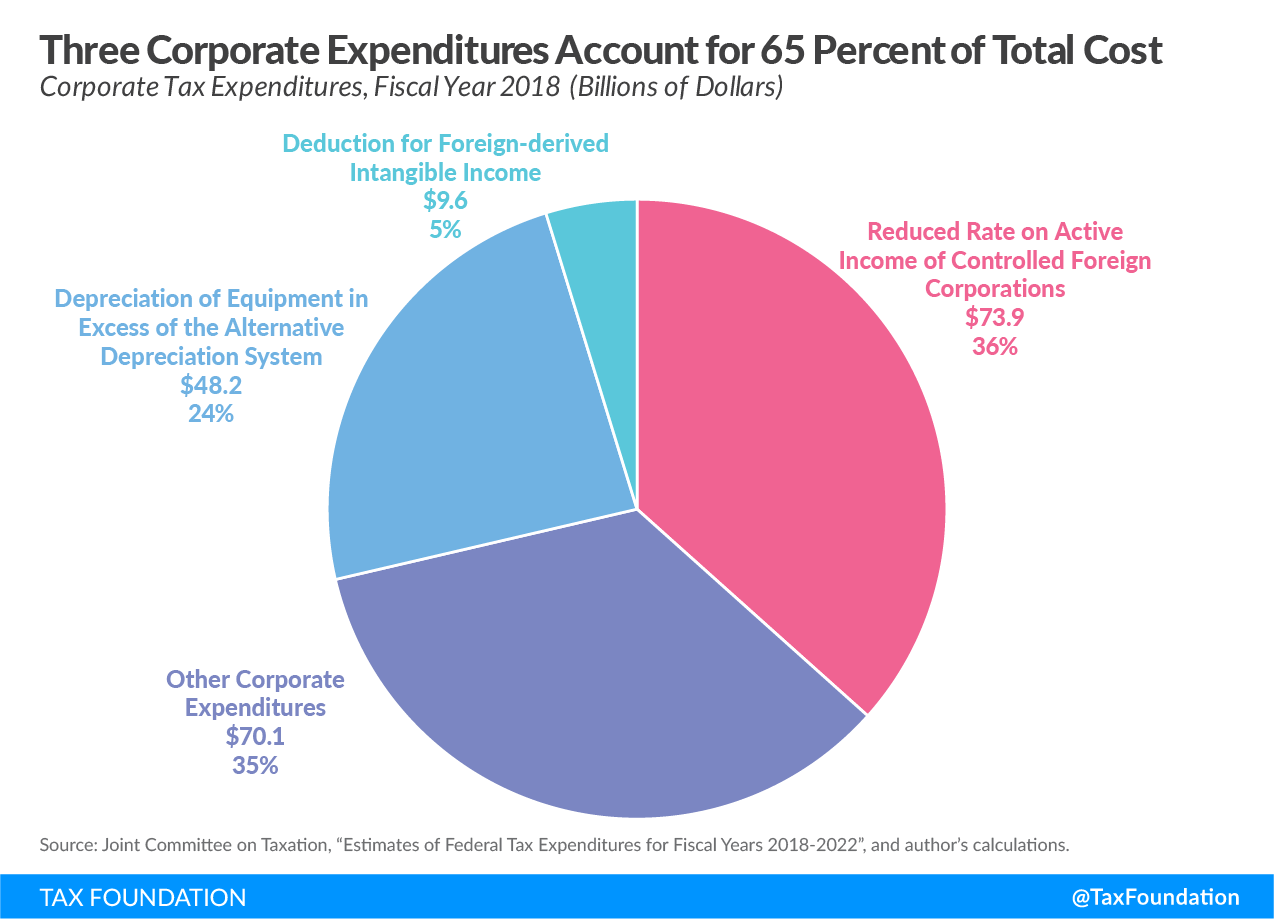

Figure 4 illustrates the largest corporate tax expenditures for fiscal year 2018. Together, the reduced tax rate on active income of controlled foreign corporations, depreciation of equipment in excess of the alternative depreciation system, and deduction for foreign-derived intangible income derived from trade or business within the U.S. make up approximately 65 percent of all corporate tax expenditures. In total, corporate tax expenditures are projected to cost $201.8 billion in 2018.

Figure 4

Three corporate tax expenditures account for 65 percent of total cost" width="1274" height="919" />

Three corporate tax expenditures account for 65 percent of total cost" width="1274" height="919" />

Before the TCJA was passed, active foreign income was usually taxed upon repatriation Tax repatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the U.S. tax code created major disincentives for U.S. companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. . Now, global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) is taxed currently, even if it is not distributed. This expenditure provides a 50 percent deduction to U.S. corporations on their GILTI. Some active income is now excluded from tax, and distributions from active income are now not taxed upon repatriation.[19] GILTI is a broad change to the tax code intended to reduce the incentive to shift corporate profits out of the U.S. by using intellectual property.

The costs of equipment and machinery are typically depreciated over time to match the reduction in economic value as equipment wears down and becomes obsolete. Depreciation of equipment ensures that net income from the property is measured appropriately each year. This expenditure provides accelerated deductions relative to economic depreciation.[20]

There is a better way to go forward. While depreciation is a useful accounting concept to calculate book values of corporations, the economic costs of an asset should be reflected by expensing; that is, the cost of the asset should be deductible in the year that the money is actually spent, properly reflecting the time value of money.[21] This is the sort of deduction that business transfer taxes or value-added taxes use, and it is in many respects much more normal than anything that the U.S. has used in the past few decades.[22]

Income earned by U.S. corporations from foreign markets would typically be taxed at the full U.S. rate. This expenditure provides a deduction worth 37.5 percent of foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). In 2026, the deduction will fall to 21.875 percent.[23]

In combination, GILTI and FDII can be thought of as a worldwide tax on deemed intangible income. They are meant to reduce incentives for companies to move the location of intellectual property to shift corporate profits out of the U.S.

Under the taxation of GILTI and FDII, U.S.-based multinational companies face roughly the same tax rate on intangibles used in serving foreign markets regardless of where those intangibles are located. If intellectual property is located in a foreign market and is used to sell products to foreign customers, it faces a minimum tax rate of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent through GILTI. If that same intellectual property is located in the United States and is used to sell products to those same foreign customers, it faces a tax rate of 13.125 percent through FDII.

The idea behind a regime including FDII and GILTI is that they are a carrot and a stick that encourages companies to place profits and intellectual property in the United States.

Table 6 lists the five corporate tax expenditures that are scheduled to expire at the end of 2018.

| Expenditure | 2018 Cost (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.” | |

| Inventory property sales source rule exception | $0.5 |

| Expensing of costs to remove architectural and transportation barriers to the handicapped and elderly | N/A |

| Deduction for income attributable to domestic production activities | $3.3 |

| Credit for Indian reservation employment | N/A |

| District of Columbia tax incentives | N/A |

| Note: JCT does not provide specific estimates for provisions that are estimated to cost less than $50 million over five years. | |

Thus, according to current law, there will be 120 corporate tax expenditures in fiscal year 2019, compared to 121 in 2017. As with individual tax expenditures, however, these estimates likely underestimate both the number and the cost of expenditures for 2019 because they do not account for the probable reauthorization of extenders.

Figure 5

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was the first large-scale reform to the federal tax code in a generation. The law lowered tax rates for individuals and corporations and included some simplifications to the associated tax bases. For instance, the standard deduction for individuals was nearly doubled to $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for married couples filing jointly in 2018. This increased the number of individuals itemizing from approximately 70 percent of filers to approximately 90 percent of filers, reducing compliance costs by $3 billion to $5 billion.[24]

However, as shown in Figure 6 below, the reforms did not reduce the number of total tax expenditures. In fact, the number of tax expenditures in 2018 is higher than it was in 2017 for both the individual and corporate tax codes. Ideally, in future tax reform efforts, Congress will work to eliminate tax expenditures.

Figure 6

As of 2018, the tax code has 173 individual tax expenditures and 125 corporate tax expenditures, with a projected cost of $1.5 trillion in 2018. Many expenditures are cases of preferential treatment for particular economic activities and therefore do not belong in the tax code. However, other expenditures play a broader and more valuable role by moving the U.S. towards another tax system. Simply eliminating expenditures across the board would therefore be misguided.

Congress has the opportunity to further the work of tax reform by ending harmful tax expenditures and instead pursuing broader improvements to the tax code. It is important to ask, for each expenditure, whether it serves a reasonable purpose and whether it accomplishes that purpose in a reasonable way. Although some tax expenditures comply with the principles of sound tax policy, many do not and deserve to be eliminated in future tax reform.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Stanley S. Surrey, “Federal Income Tax Reform: The Varied Approaches Necessary to Replace Tax Expenditures with Direct Governmental Assistance,” Harvard Law Review 84(2), December 1970, 352, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1339715?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

[3] Henry C. Simons, Personal Income Taxation: The Definition of Income as a Problem of Fiscal Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1938). See also Robert M. Haig, “The Concept of Income—Economic and Legal Aspects,” in Robert M. Haig, The Federal Income Tax (New York: Columbia University Press, 1921).

[4] Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957), https://econpapers.repec.org/bookchap/nbrnberbk/frie57-1.htm.

[5] Michael Schuyler, “Baked In the Cake: Why the Progressivity of the Income Tax Isn’t Visible in the Distribution of Tax Expenditures,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 13, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/baked-cake-why-progressivity-income-tax-isn-t-visible-distribution-tax-expenditures.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5148.

[7] For an example of the limitations of this definition, consider a tax plan that increases individual income taxes on corporate income by a percentage point, but reduces corporate income taxes by a percentage point. Most observers would say this is an inconsequential plan that mostly cancels itself out, but it would be a reduction in tax expenditures under JCT’s definition.

[8] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[10] Following JCT protocol, this analysis does not consider expired tax expenditure provisions unless they have continuing revenue effects associated with ongoing taxpayer activity. Additionally, like the JCT, this analysis does not consider the cost of tax expenditures for fiscal year 2018 that result in revenue losses less than $50 million over fiscal years 2018-2022. For more information, see Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022.”

[11] Erica York, “Recommendations to Congress on the 2018 Tax Extenders,” Tax Foundation, April 17, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/2018-tax-extenders.

[15] Norman B. Ture and Stephen J. Entin, “The Inflow Outflow Tax – A Saving-Deferred Neutral Tax System,” Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, 1997, http://iret.org/pub/inflow_outflow.pdf.

[16] Erica York, “Recommendations to Congress on the 2018 Tax Extenders.”

[17] There is some overlap between individual and corporate tax expenditures, as some expenditures, such as the limitation on net interest deduction to 30 percent of adjusted taxable income, can be utilized to offset both individual and corporate income taxes.

[18] Erica York, “Recommendations to Congress on the 2018 Tax Extenders.”

[19] U.S. Treasury, “Tax Expenditures,” 4.

[21] Stephen J. Entin, “The Tax Treatment of Capital Assets and Its Effects on Growth: Expensing, Depreciation, and the Concept of Cost Recovery Cost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker ’s productivity and wages. in the Tax System,” Tax Foundation, April 24, 2013, https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/bp67.pdf.

[22] Unlike a business tax code with depreciation schedules, a business tax code with expensing can easily determine the appropriate size of deductions. It simply bases them on actual cash flow, a method that is neutral across all business.

[23] U.S. Treasury, “Tax Expenditures,” 4.